Follow me on Twitter @JoshACorman

We here at the Infusion know that you want a little culture in your life. We know that’s why you listen to at least six minutes of classical music per month on that one classical station that’s kind of close to NPR on the radio dial. We know that’s why you go to bookstores and admire the covers of all those nice new Penguin editions on the “classics” table. Thankfully, you’ve got us to supplement your other, er... efforts at embiggening your inner life.

Our first cultural inoculation (little known fact: Cultural Inoculation was in the running for this site’s name, but its lack of tea-centric humor cost it dearly) involves one of the greatest works in American literary history. Now, before we get started in earnest, let me set your mind at ease. This isn’t senior English, and I’m not giving a pop quiz. Quite the opposite, in fact. There exists a very real dilemma in the lives of astute/educated/culturally aware/bookish people: we legitimately have an interest in the canon. Whether films, books, albums, paintings, sculptures, sonnets, limericks, or soup cans, we want to know what all the fuss is about regarding all those supposedly great things we see listed in magazines or blogs as “The Greatest of All Time.” Our interest in these things creates a problem because we know that we can’t possibly get to it all. Sad, but true. I mean, I’d love to spend more time watching Truffaut films or listening to Woody Guthrie recordings (seriously), but I’ve got enough on my plate keeping up with Wes Anderson and Josh Ritter. I know Truffaut is hugely influential, but what if I watch The 400 Blows and it, well, blows (if you're thinking, 'Corman's better than that joke,' you're wrong)? Then I’ve wasted valuable capital that can’t be refunded. “That’s right!” I hear you saying. “If only I had someone who I trusted implicitly to guide me through the mine field of Important Cultural Decisions (ICDs).” Well, here I am! You’re welcome, Mom (sorry, but until it’s proven to me that someone besides my mom is reading these...).

Today, I’d like to answer just one question that will make your cultural life that much easier: Should you read Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn?

Well, yes, you should. And I’ve got five simple reasons as to why.

1. Hemingway’s right, you know.

Hemingway (or Owen Wilson, if you follow Woody Allen’s version of history) famously called Huck Finn the apotheosis of the American novel. Being Hemingway, he used shorter words, but you get the idea. Point is, he’s right. Think about it: the novel is set on America’s greatest body of water, it offers commentary on one of our most important moral episodes, and was written by perhaps our most recognizable and quintessentially American author.

Now, some of you might counter my Hemingway with a seemingly appropriate Twain quote: “A classic is a book which everyone wants to have read, but no one wants to read.” The problem with using Twain as a defense in this case is that you would have to do it ironically, but since the quote itself is ironic, it cancels out, just like two negatives in that one branch of math I remember almost nothing about.

2. Huck is the Most Significant Character in the History of our Culture.

Bart Simpson. Marty McFly. Ferris Bueller. These are the great-grandchildren to Huckleberry Finn. We love the precocious, street-smart youngster who has to outwit the establishment in the name of adventure, and Huck provides the blueprint. He’s arrogant, more than a little selfish, ballsy, but ultimately can’t help doing the right thing. Sound familiar? Let’s add another character to that list, shall we: Han Solo. Bam! What red-blooded American could resist taking an adventure with the spiritual great-grandfather to Ferris Bueller and Han Solo? So what if a raft replaces the red Ferrari (so choice) and the Millenium Falcon? So what if a runaway slave named Jim replaces that whiny malcontent Cameron and Chewbacca? Abe Frohman, Sausage King of Chicago, and the captain of the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs would be disappointed in you for worrying about sexiness over substance. So go forth, hop aboard the raft with Huck, and spend a couple hundred pages with a mostly naked, nearly illiterate thirteen-year-old who smokes like a chimney. (Wait, did I just undercut my case? Moving on.)

Hemingway (or Owen Wilson, if you follow Woody Allen’s version of history) famously called Huck Finn the apotheosis of the American novel. Being Hemingway, he used shorter words, but you get the idea. Point is, he’s right. Think about it: the novel is set on America’s greatest body of water, it offers commentary on one of our most important moral episodes, and was written by perhaps our most recognizable and quintessentially American author.

Now, some of you might counter my Hemingway with a seemingly appropriate Twain quote: “A classic is a book which everyone wants to have read, but no one wants to read.” The problem with using Twain as a defense in this case is that you would have to do it ironically, but since the quote itself is ironic, it cancels out, just like two negatives in that one branch of math I remember almost nothing about.

2. Huck is the Most Significant Character in the History of our Culture.

Bart Simpson. Marty McFly. Ferris Bueller. These are the great-grandchildren to Huckleberry Finn. We love the precocious, street-smart youngster who has to outwit the establishment in the name of adventure, and Huck provides the blueprint. He’s arrogant, more than a little selfish, ballsy, but ultimately can’t help doing the right thing. Sound familiar? Let’s add another character to that list, shall we: Han Solo. Bam! What red-blooded American could resist taking an adventure with the spiritual great-grandfather to Ferris Bueller and Han Solo? So what if a raft replaces the red Ferrari (so choice) and the Millenium Falcon? So what if a runaway slave named Jim replaces that whiny malcontent Cameron and Chewbacca? Abe Frohman, Sausage King of Chicago, and the captain of the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs would be disappointed in you for worrying about sexiness over substance. So go forth, hop aboard the raft with Huck, and spend a couple hundred pages with a mostly naked, nearly illiterate thirteen-year-old who smokes like a chimney. (Wait, did I just undercut my case? Moving on.)

|

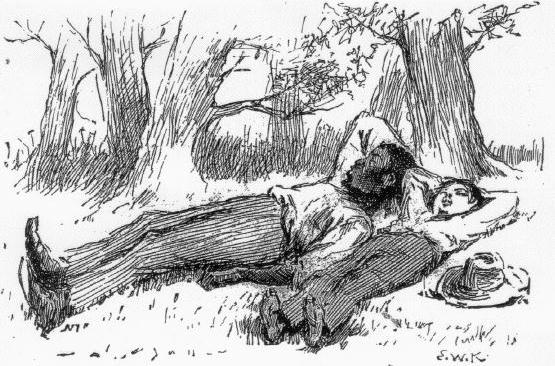

| Getting a copy with the original illustrations is worth it. |

3. All Other Literary Sins can be Forgiven if You’ve Read Huck Finn.

Let’s imagine that dinner parties were still things. What’s that, you say? Really? They are, huh? Weird.

OK, so let’s imagine that you’re at an actual dinner party, which is allegedly still a real occurrence. Somebody brings up Crime and Punishment, The Grapes of Wrath, The Great Gatsby, Pride and Prejudice, or one of the other few hundred novels that people wear like talismans around their necks once they get around to finishing them. You say, “You know, I’ve never actually read (insert classic here), but I read Huck Finn not too long ago, and it was fantastic; I don’t know how anyone’s ever called that a story for children." This accomplishes two vital goals: one, it immediately makes everyone around you forget that you haven’t read some other book whose title they can’t even recall at the moment, and two, it puts the pressure on everyone else listening to either ‘fess up to not having read this most seminal American work or find something very interesting across the room that they must attend to suddenly. Remember, they’re called the Culture Wars, and you need to win.

4. It’s Just So Much Fun

Let me get something out of the way: Huck Finn is not A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy or even Slaughter-House Five. It is, however, better than both of those books and nearly as funny. But this isn’t about how funny the book is; it’s about how much fun the book is. Its cast of characters rivals (and probably trumps) anything Dickens ever put to the page, and its plot (don’t tell Twain you were looking for one) is simultaneously thrilling, frightening, hilarious, and suspenseful. For all the value I place on putting in the (sometimes difficult) work necessary to enjoy great art, Huck Finn, rich though it is, requires surprisingly little effort to enjoy. This doesn’t mean it’s simplistic, just that Twain so expertly executes his purpose that as you kick back on your porch (if you don’t have a porch on which to read Huck Finn, I suggest you engage in some minor trespassing, just to ensure the full effect), Twain’s wit and charm lift literary revelations right off the page and lay them at your feet, ready for your chewing pleasure.

Warning: If you attempt to read this novel on a summer evening while smoking a pipe, reclining near a body of water, or chewing on a stem of wild grass, you may collapse in a fit of sheer pleasure.

5. If Nothing Else...

- You need to know what all this n-word hubbub is about. That scoundrel from Auburn who’s aiming to censor Huck (and make a tidy profit from his own edition of the novel) deserves to be yelled at, but only by people who know why they’re yelling.

- It’s hundreds of pages shorter than other works that your friends have been pestering you to read. The $2.00 Dover Edition runs 220 pages, unabridged.

- I nearly drowned a certain unnamed friend of mine in a certain famous river in a certain major British city because he admitted to never having read Huck Finn. Protect yourself from nut-jobs like me and read the damn book already.

By Josh Corman

Follow me on Twitter @JoshACorman

2 comments:

"Oh please, embiggens is a perfectly cromulent word!"

Scrumtralescent, if I say so myself.

Post a Comment