|

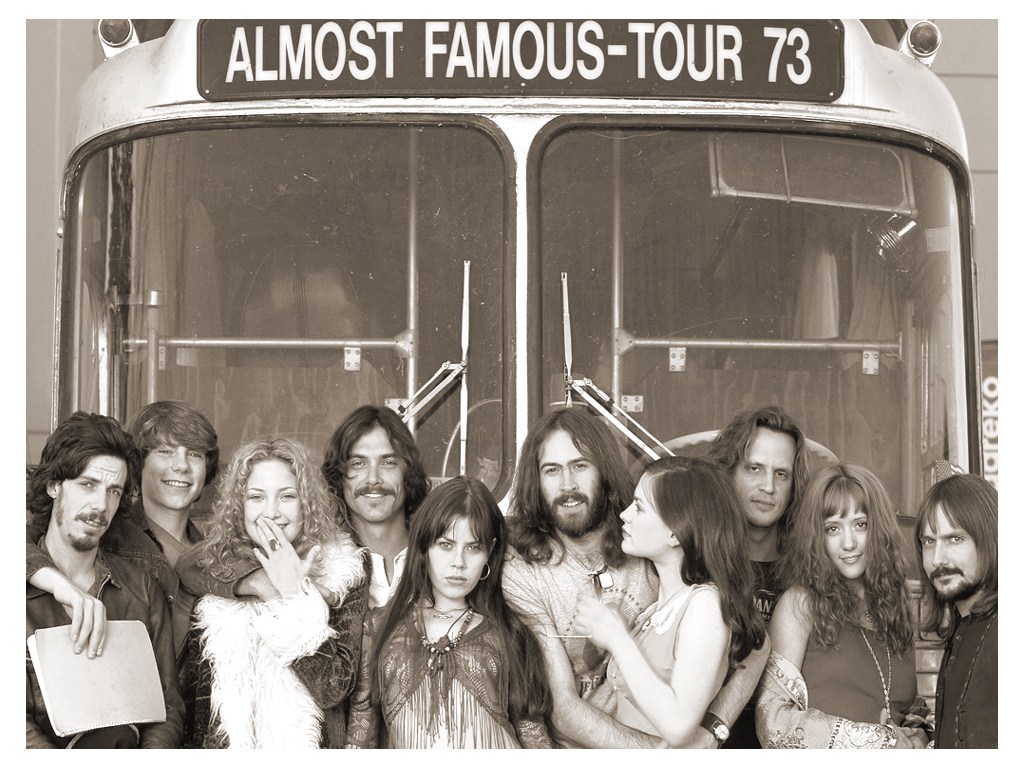

| One of these things is not like the others. |

Follow me on Twitter @JoshACorman

By Josh Corman

I once tried to write about Cameron Crowe.

What I Wish Had Happened: I poured myself a drink, brought a stack of records to the desk, threw on side one of Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, cracked my knuckles, and typed without stopping (except to flip the record or raise my glass, of course) on my Smith-Corona Galaxie XII typewriter until I had produced nearly 2,000 flawless words about a man in whom I am very much interested, the venerable Mr. Cameron Crowe.

You see, if I were writing about Cameron Crowe, I would have to get myself into a Cameron Crowe state of mind (or so the logic went).

What Really Happened: I curled up in my bed, secluded (the better to concentrate, I told myself), intent on writing about Cameron Crowe. No drink, no vinyl, no typewriter. There may have been 2,000 words somewhere along the line, but most of them are deleted. Three or four different false starts later, I finally scrapped the piece and rescued something from my “works in progress” folder and shaped it up for a residence on this site.

What’s Happening Now: More than a month later, I sit at my desk, having at it one more time. Drink: yes. Records: no (iTunes will have to do). Typewriter: Never even owned one. Cameron Crowe: Finally, yes.

“The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with somebody when you are uncool.”

Go ahead, read it again.

One more time. Seriously.

If you’ve got guts, read it aloud.

I’ll give you a minute.

...

Let me just tell you that there are some things I wish that I’d written. As far as single sentences go, that one is at the top of my list. The profound sense of envy I feel about not having written that line is compounded by my even more profound envy I have towards the person who actually did write it. You guessed it: Cameron Crowe.

The bastard.

The line, delivered by Philip Seymour Hoffman’s note-perfect Lester Bangs, comes from Crowe’s magnum opus, Almost Famous, which loosely recreates Crowe’s teenage years when he scored a job writing for Rolling Stone and toured the country with The Allman Brothers’ Band, Led Zeppelin, Neil Young, and The Who. OK, so envy doesn’t adequately describe the feeling. I actually feel wronged by Cameron Crowe, like he’s cheated me out of experiences that I might have, nay, should have gloriously lived out if I had been a fifteen-year-old prodigy in Southern California in 1973. I should hate the guy, right? I should find his films insufferable or pretentious. The schadenfreude potential is enormous, folks.

But I actually kind of love him.

And it isn’t that Crowe is a particularly great director. He’s good, certainly. He’s got a (usually) deft ear for clever dialogue (Lloyd Dobler’s career speech in Say Anything; most of Jerry Maguire and Almost Famous), he’s crafted his share of memorable moments (Say Anything’s so-iconic-as-to-have-suffered-the-unjust-fate-of-becoming-overrated “boombox scene,” the “You had me at hello” and “Show me the money!” scenes from Jerry Maguire, the “Tiny Dancer” scene from Almost Famous) and characters (Dobler; Maguire, nearly everyone in Almost Famous), and he’s got a bold streak to boot (Vanilla Sky).

Despite this respectable accumulation of artistic achievement, Crowe routinely falls short of greatness. His movies are almost always too long, the plots are frequently circuitous to the point of distraction (even his masterpiece is guilty, though I’m charmed rather than annoyed by it in that case), and he’s drawn stilted performances from his lead actors on more than one occasion (Renee Zellweger in Maguire, Orlando Bloom in Elizabethtown). Even his oft-praised encyclopedic knowledge of—and deep-seated love for—pop music has grown into as much of a crutch as a weapon.

So he’s what, a middle-aged director with a huge stack of vinyls who charts at the high end of average and who only puts out slightly more than two films a decade?

Well, no. Not quite. That is, he may be those things, but he also possesses at least one other salient quality that keeps me from dismissing the guy as a one and two-halves hit wonder as some of the “serious” film-going world has. The best illustration of this particular quality is Crowe’s much-maligned (as in, the professional and amateur film critics of the world got together and voted to enact a social mandate threatening a public flogging to anyone who expressed genuine appreciation for this film; see M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village) 2005 pet project, Elizabethtown.

The movie tells the story of a prodigal son’s journey (warning!) to retrieve his father’s body (repeat: warning!). On the way, he meets a quirky flight attendant (WARNING!) who opens his eyes (For the love of God, somebody do SOMETHING!) to the spirit of adventure and empathy (CRASH!), and leads him via mix-tape on a cross-country journey of self-discovery. (That sound you hear is the orchestra still playing as the icy water slowly fills the ruptured hull of the Titanic.) Elizabethtown is, by any measure, an act of self-indulgent directorial gluttony. I should hate this movie, just like most people do.

But I actually kind of love it.

That quality of Crowe’s I mentioned earlier can best be described as a painfully earnest desire to get to the root of what makes us afraid of the world around us, and it positively drips from Elizabethtown. Orlando Bloom’s character (Drew Baylor) is emotionally able to go on his film-ending road trip only after suffering a spectacular, career-ending failure, being harassed by his family into realizing that he barely knew his father, and having all of his sophisticated affectations exposed by a series of people who challenge the one thing he clings to most fiercely: his coolness. There, I suspect, lies some of the explanation for the vitriol surrounding Elizabethtown. We see movies where a loss of cool is necessary for a character’s self-realization as trite and cheesy. As the parent of a two-year-old, I can vouch for the stunning number of children’s movies in which this same general character arc is present.

If the connection seems flippant, I’m sorry. It isn’t meant to be. We associate the themes Crowe so often explores as childish and unworthy of serious adult consideration, especially when they’re explored as un-ironically as Crowe does in his films. I say films because when I think about it, every film of his that I’ve seen (all but Singles and the newly released We Bought a Zoo) features a character who is stripped of his cool on his way to the tale’s climax. In Say Anything, it’s Dianne (Ione Skye’s character) whose Class President sheen is stripped away as she fumbles her way through normal social experiences and her relationship with her father crumbles. Jerry Maguire falls from grace and is rescued from professional and relational hell only after making a fool of himself on a grand scale and realizing that he isn’t too good for his wife. Both Penny and Russell in Almost Famous are nearly reduced to rubble before their epiphanies arrive. Even in Vanilla Sky, a film he didn't write, David Aames is brought low from his days as an invincible playboy by a relationship he plays a little too coolly.

Why does any of this matter? How does it make Cameron Crowe anything more than a mediocre director who’s a total sap on top of everything else? It matters because I hold a special place in my heart for people who really, violently mean what they say, even when what they say is on the hokey side. It’s the same reason I love Bob Dylan and Neil Young despite the considerable gap between their artistic ambition and the quality of their voices. They mean what they sing so intensely that their depth of feeling overcomes flaws that seem more and more inconsequential the more you listen to their music.

If Dylan and Neil were cool, they would never have opened their mouths. If Lloyd Dobler were cool he would have never blasted “In Your Eyes” from that boom box to a girl who’d broken his heart. If Jerry McGuire were cool, he never would have saved his marriage. Russell Hammond wouldn’t have given William that final interview. Drew Baylor never would’ve truly appreciated his father. These people can't be saved as long as they're cool. Cameron Crowe believes fundamentally that coolness is a false currency, a shield that we use to protect ourselves from the most frightening, vital aspects of the world around us, and he can’t help but show us how fervently he believes it, over and over again. You know why?

Let me just tell you that there are some things I wish that I’d written. As far as single sentences go, that one is at the top of my list. The profound sense of envy I feel about not having written that line is compounded by my even more profound envy I have towards the person who actually did write it. You guessed it: Cameron Crowe.

The bastard.

The line, delivered by Philip Seymour Hoffman’s note-perfect Lester Bangs, comes from Crowe’s magnum opus, Almost Famous, which loosely recreates Crowe’s teenage years when he scored a job writing for Rolling Stone and toured the country with The Allman Brothers’ Band, Led Zeppelin, Neil Young, and The Who. OK, so envy doesn’t adequately describe the feeling. I actually feel wronged by Cameron Crowe, like he’s cheated me out of experiences that I might have, nay, should have gloriously lived out if I had been a fifteen-year-old prodigy in Southern California in 1973. I should hate the guy, right? I should find his films insufferable or pretentious. The schadenfreude potential is enormous, folks.

But I actually kind of love him.

And it isn’t that Crowe is a particularly great director. He’s good, certainly. He’s got a (usually) deft ear for clever dialogue (Lloyd Dobler’s career speech in Say Anything; most of Jerry Maguire and Almost Famous), he’s crafted his share of memorable moments (Say Anything’s so-iconic-as-to-have-suffered-the-unjust-fate-of-becoming-overrated “boombox scene,” the “You had me at hello” and “Show me the money!” scenes from Jerry Maguire, the “Tiny Dancer” scene from Almost Famous) and characters (Dobler; Maguire, nearly everyone in Almost Famous), and he’s got a bold streak to boot (Vanilla Sky).

Despite this respectable accumulation of artistic achievement, Crowe routinely falls short of greatness. His movies are almost always too long, the plots are frequently circuitous to the point of distraction (even his masterpiece is guilty, though I’m charmed rather than annoyed by it in that case), and he’s drawn stilted performances from his lead actors on more than one occasion (Renee Zellweger in Maguire, Orlando Bloom in Elizabethtown). Even his oft-praised encyclopedic knowledge of—and deep-seated love for—pop music has grown into as much of a crutch as a weapon.

So he’s what, a middle-aged director with a huge stack of vinyls who charts at the high end of average and who only puts out slightly more than two films a decade?

Well, no. Not quite. That is, he may be those things, but he also possesses at least one other salient quality that keeps me from dismissing the guy as a one and two-halves hit wonder as some of the “serious” film-going world has. The best illustration of this particular quality is Crowe’s much-maligned (as in, the professional and amateur film critics of the world got together and voted to enact a social mandate threatening a public flogging to anyone who expressed genuine appreciation for this film; see M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village) 2005 pet project, Elizabethtown.

The movie tells the story of a prodigal son’s journey (warning!) to retrieve his father’s body (repeat: warning!). On the way, he meets a quirky flight attendant (WARNING!) who opens his eyes (For the love of God, somebody do SOMETHING!) to the spirit of adventure and empathy (CRASH!), and leads him via mix-tape on a cross-country journey of self-discovery. (That sound you hear is the orchestra still playing as the icy water slowly fills the ruptured hull of the Titanic.) Elizabethtown is, by any measure, an act of self-indulgent directorial gluttony. I should hate this movie, just like most people do.

But I actually kind of love it.

That quality of Crowe’s I mentioned earlier can best be described as a painfully earnest desire to get to the root of what makes us afraid of the world around us, and it positively drips from Elizabethtown. Orlando Bloom’s character (Drew Baylor) is emotionally able to go on his film-ending road trip only after suffering a spectacular, career-ending failure, being harassed by his family into realizing that he barely knew his father, and having all of his sophisticated affectations exposed by a series of people who challenge the one thing he clings to most fiercely: his coolness. There, I suspect, lies some of the explanation for the vitriol surrounding Elizabethtown. We see movies where a loss of cool is necessary for a character’s self-realization as trite and cheesy. As the parent of a two-year-old, I can vouch for the stunning number of children’s movies in which this same general character arc is present.

If the connection seems flippant, I’m sorry. It isn’t meant to be. We associate the themes Crowe so often explores as childish and unworthy of serious adult consideration, especially when they’re explored as un-ironically as Crowe does in his films. I say films because when I think about it, every film of his that I’ve seen (all but Singles and the newly released We Bought a Zoo) features a character who is stripped of his cool on his way to the tale’s climax. In Say Anything, it’s Dianne (Ione Skye’s character) whose Class President sheen is stripped away as she fumbles her way through normal social experiences and her relationship with her father crumbles. Jerry Maguire falls from grace and is rescued from professional and relational hell only after making a fool of himself on a grand scale and realizing that he isn’t too good for his wife. Both Penny and Russell in Almost Famous are nearly reduced to rubble before their epiphanies arrive. Even in Vanilla Sky, a film he didn't write, David Aames is brought low from his days as an invincible playboy by a relationship he plays a little too coolly.

Why does any of this matter? How does it make Cameron Crowe anything more than a mediocre director who’s a total sap on top of everything else? It matters because I hold a special place in my heart for people who really, violently mean what they say, even when what they say is on the hokey side. It’s the same reason I love Bob Dylan and Neil Young despite the considerable gap between their artistic ambition and the quality of their voices. They mean what they sing so intensely that their depth of feeling overcomes flaws that seem more and more inconsequential the more you listen to their music.

If Dylan and Neil were cool, they would never have opened their mouths. If Lloyd Dobler were cool he would have never blasted “In Your Eyes” from that boom box to a girl who’d broken his heart. If Jerry McGuire were cool, he never would have saved his marriage. Russell Hammond wouldn’t have given William that final interview. Drew Baylor never would’ve truly appreciated his father. These people can't be saved as long as they're cool. Cameron Crowe believes fundamentally that coolness is a false currency, a shield that we use to protect ourselves from the most frightening, vital aspects of the world around us, and he can’t help but show us how fervently he believes it, over and over again. You know why?

Because Cameron Crowe is uncool.

By Josh Corman

Follow me on Twitter @JoshACorman

3 comments:

I'm so uncool that I'm the first commenter on my own piece.

Last night, I finished this, got in bed, and turned on The Daily Show. What did I see in their second segment?

A spoof of Say Anything.

Say what you will, but the man has irrevocably wiggled his way into the culture.

This really good but the Rolling Stones are really cool, so that sort of complicates things.

My friend Aaron said it best: I want to punch the makers of Elizabethtown in the face, but then give them a big hug.

Post a Comment